RE: Apple, Its Control Over the iPhone, The Internet, And The Metaverse

Note to readers: This is a rejoinder to Matthew Ball's epic 15000-word essay of the same title, published on February 2, 2021. He was gracious enough to reply to my initial concerns on Twitter, and he did stop by to read this.

It is not often that someone takes effort to pen a long-form piece of about 30-pages on Apple (Matthew says the essay took several months to write), but because it concerns Apple, the details matter.

I have never worked with or for Apple, neither do I own Apple stock, but as someone who has been in the industry for long enough, I can say that Apple would easily be at the top of a list of the most detailed-oriented companies, if such a list were to exist. Perhaps this is also why their actions and in-actions are grossly misunderstood.

Chapter One: The Creation of Today’s Internet and the Needs of Tomorrow’s

In chapter one, Matthew writes that:

Services like Zoom also work because they leverage actively maintained standards that are free to use and designed to support any device.

I totally understand that this essay may have been written to be accessible to a lay person, but the problem with this claim is that, it doesn't tell the full story.

A lot of video conference call invites are accepted via email, and if you are doing it for the first time, you'll likely not have the Zoom client installed on your machine, so yes, Zoom has to "leverage actively maintained standards" to make a good first impression, when all a first-time user has installed is a web browser.

But as your needs expand, so will your desire to explore the best they have to offer–at which point they can nudge you towards their more powerful services, which are of course not built on (open) standards.

He also writes that:

But just imagine, for example, how the internet might differ if it had been created by multinational media conglomerates in order to sell things, serve ads or harvest user data for profits. Downloading a .JPG could cost money, with a .PNG costing 50% more. Teleconferencing software might have required the use of a broadband operator’s app or portal (e.g. Welcome to your Xfinity Browser™, click here for Xfinitybook™ or XfinityCalls™ powered by Zoom™). Websites might only work in Internet Explorer or Chrome - and need to pay a given browser an annual fee for the privilege.

The fascinating thing about this passage is that, every single hypothetical idea he doesn't wish to entertain has been used in the past, successfully.

Yes, downloading a .JPG or images in general, did in fact cost money when Internet usage wasn't yet wide spread. Although, you didn't pay for each image directly, the cost of your web browsing was reflected in your phone bill, because back then, the main way to access the Internet was via phone modems.

To corroborate what I'm saying, here's a June 28, 1994 entry on the topic from the NY Times titled PERSONAL COMPUTERS; You Can't Roller-Skate On Electronic Highway. Below is an excerpt:

Although the general rule in modems is "the faster the better," there are several reasons a cautious computer user might wisely choose a slower 14.4 kilobit-per-second modem over the V.34 speedsters.

The first is cost. As with any new technology, the pioneers pay the price. The new modems typically cost $500 or more, as against $100 to $150 for the 14.4-kilobit modems.

Due to the cost implications, it was not uncommon to browse the Web image-free via the "Do not show any images" browser setting, especially because a lot of dial-up modems were very slow anyway.

If you substitute Xfinity with AOL, the hypothetical scenario he paints about portals was in fact the lived experience for millions of first-time Internet users, as succinctly captured by this NY Times article from 1996:

But the follow-up study also found that 20 percent of the people who said they had access to the Internet in the first survey said they no longer had access six months later. Of those who did visit the Internet, most did so through commercial on-line services like America Online, the study found. America Online promises to connect users with a minimum of technical difficulty, which attracts inexperienced computer users.

''It makes sense, because the usage of people who go on line through a commercial service tends to be more personal and more periodic,'' said Thomas E. Miller, vice president of the emerging technologies research group of Find/SVP, a market research firm in New York. ''AOL has succeeded in penetrating a downscale audience.''

With respect to web browsers:

Websites might only work in Internet Explorer or Chrome -

Best viewed with Internet Explorer was an actual thing, it even had a logo to go with it that should be instantly recognizable to early netizens.

... and need to pay a given browser an annual fee for the privilege.

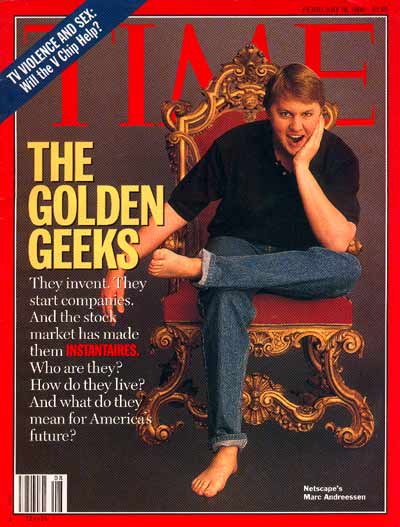

Today, Matthew may balk at the idea of paying for a web browser, but people back then certainly didn't. Many may know Marc Andreessen as promoter of VC firm Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), but in the Feb. 19, 1996 issue of Time Magazine, he appeared on the cover.

What was his claim to fame? You guessed it–a successful IPO from an Internet business that initially made money from selling web browsers for $40 a pop!

Chapter Two - Three

Similar to Chapter 1, there are several historical inaccuracies in Chapters 2 - 3.

It's okay to make mistakes since no one can know everything about our computing past. I'll skip them, particularly because it is merely part of the build up to the meat of the essay. Besides, I'm trying to avoid making this piece too long.

Chapter Four: Apple’s Deficient Monopoly Defenses

Lastly, it’s notable that while MacOS does not have iOS’s restrictions on software/app installations, it remains secure and safe to use. This is because the majority of security is held at the kernel/OS-level. To this end, malicious apps (and updates) have lengthy history of making it through the App Store review. This is inevitable given the volume of submissions, time spent reviewing code, and human error rates, but crucially, these bad actor apps don’t destroy the device or devour private files (as is often the case with Windows malware). This is because of iOS’s system and API-level security, which is a stronger and more scalable solution - and one that offers consumers more choice and developers more capabilities.

The reason why there's a disparity in security incidents between macOS and iOS isn't far fetched. As far as devices go, there are way more iOS users than there are macOS users, which causes attackers to focus on iOS because of the incredible ROI.

It is true that iOS doesn't allow third-party browser engines, but there are tricky engineering details behind why Apple made this trade off. I'd love to delve into it here, but based on the outline I wrote, it deserves to be written as a standalone piece. Including it here would make this rejoinder nearly as long as the original ~30-page essay.

Chapter Five: The Importance of Prioritizing Overall Prosperity

Why does this matter? How much should we really care about how apps are made and who gets paid for them? Or the platforms that are used or allowed? Or who can advantage which identity solution, service, or standard? The answer is that we have to care. In 2021, almost every company is a digital company, and the scope, significance, and complexity of the digital/virtual world continues to expand.

To prosper, new winners must be able to emerge at every layer of the “new economy” and without being constrained by what a single company envisions or wants. The current situation isn’t terrible — great things are happening in terms of users, creators, and innovation. But the very decisions that have made Apple so successful today also limit the number of creators that participate in the virtual economy, handicap the creativity of their products and business models, and make every transaction more expensive. Most important, it is blocking the organic evolution of the overall Internet.

I don't understand the logic here. Let's zoom out by focusing on another technology company that makes physical goods and is using an integrated approach: Tesla.

Tesla, like Apple, tries to own every part of the experience: the car, the (expensive) battery, the car charging network, the in-car operating system called Tesla Software (a corollary to iOS), a soon to be launched app store, and of course they own what would have been the car distribution via traditional car dealerships.

Similar to Apple, there is one exception to this integrated approach that they do not try to own or control: the ecosystem around accessories. Tesla has a growing ecosystem for accessories:

Today, Elon Musk is worth $186.5B, a large part is due to his Tesla holding, and if they continue on their current trajectory (read: their competitors take too long to figure out electric in a way that is viable), they might go on to dominate not just the electric car, but the car industry as a whole.

The Tesla in-car OS currently supports apps for Spotify, Netflix, YouTube, and Hulu, and I imagine that list will continue to grow. Assuming they go on to dominate the car industry, somehow by some logic that is not clear to me, they should be compelled to allow on all Teslas, third-party OSes or third-party app stores that compete with Tesla OS or its app store?

In other words, Apple CarPlay and Android Auto, which are competing car OSes designed for general purpose cars (each with its own marketplace), should somehow be allowed to be installed on Teslas because Tesla is hypothetically the dominant car maker, but not on competitor cars because those are not monopolies?

Tesla's hypothetical blocking of third-party app stores would somehow be "blocking the organic evolution of the overall car industry"? Even though they are not the only car seller, they just happen to be the most dominant? Which law or moral code would they be violating?

No car-maker has ever been subjected to such logic, at least with respect to their in-car OS, so I don't understand this logic at all or how it should somehow apply to Apple's iOS.

If Apple's iOS wielded a monopoly on all mobile devices, irrespective of device maker similar to Microsoft Windows at its peak, then this would be a clear case of monopoly power being wielded that needs to be curbed.

I suspect people are leaning too much on the desktop PC and its attendant metaphors, to reason about how the ecosystem should be around mobile products.

Chapter Six: Solving the Apple Problem

Apple has the right to run its own store, offer its own standards, and develop services that are exclusive to its hardware. The problems arise from Apple’s forced bundling of hardware, an operating system, distribution system, payment solution and services. As a result, there is a straightforward remedy — forcing Apple into competition in app distribution and payments.

I'm not sure I understand what is being advocated here. Apple's operating philosophy has always been to offer an integrated experience as opposed to the less integrated experience of Wintel; where Microsoft makes the operating system (OS), Intel makes the computer chip, while Original Equipment Manufacturers or OEMs make the rest of the computer.

This is not some new approach, it has always been how they approach the design their products. In fact, at the 2007 launch of the iPhone (0:40s YouTube clip), Steve Jobs attributed how they think about technology products to a quote from 40 years ago (Apple is 45 years old) by Alan Kay, a highly respected computing pioneer:

People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware. – Alan Kay

When the dominant metaphor was desktop computing, Apple competed against Windows on the desktop by offering an integrated experience and nearly went bankrupt in 1997. The market voted with their wallets because they favored the less integrated approach of Wintel. Of course, there were a lot of factors at play.

Today, the dominant metaphor is mobile computing. In 2007, Apple was the underdog with 0% market share in mobile, but it didn't deter them from using the same integrated approach against two massive incumbents–smartphone vendors Nokia and BlackBerry.

Nokia, with the largest market share, made the device, open-source OS, app store and allowed the loading of apps from third-party app stores–if you know how.

BlackBerry, with the next largest market share, also made the device, proprietary OS and app store. They didn't officially allow loading of apps from third-party app stores, but like Nokia, the process was convoluted anyway.

Each had a lot of similarities to Apple's integrated approach of software, hardware and services, but Nokia and BlackBerry lost to Apple, not because they were a monopoly (they were the underdog), but because the market valued Apple's interpretation of what an integrated experience should look like more than theirs. Simple market economics is at play here, nothing else.

Users who value the existence of a viable third-party app store ecosystem over an integrated experience can always use Google Android. Anyone else who feels left out, can always seek VC funding to start an Android or iPhone killer, and let the market decide.